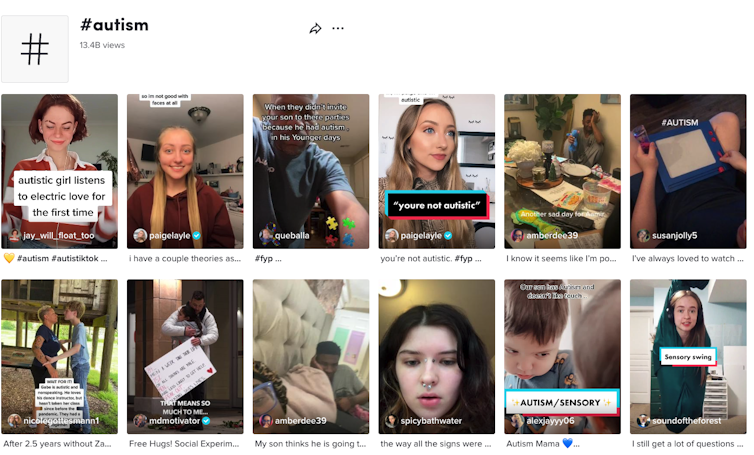

A quick look at some TikTok stats shows more than 38,000 posts under the hashtag #Autism, with more than 200 million views. The hashtag #ActuallyAutistic (which is used in the autism community to highlight content created by, and not about, autistic people) has more than 20,000 posts and 40 million views.

TikTok is one of the world’s leading social platforms, and has exploded in popularity at a time when other social media megaliths have struggled. It has become an important channel for expression for its young usership – and this has included giving autistic people a voice and community.

It’s a good start. In some ways TikTok has helped drive discussions around autism forward, and shift outsiders’ perspectives. But for real progress, we have to ensure “swipe up” environments aren’t the only spaces where autistic people are welcomed.

But first, what is autism?

Autism is not an illness or a disease. It’s a lifelong developmental condition that occurs in about one in 70 people. Characteristics of the condition occur along a spectrum. This means there is a wide range of differences among people with autism, all of whom have unique challenges and strengths.

A 2017 survey conducted by myself and my colleagues found more than half of autistic people and their family members felt socially isolated. And 40% said they sometimes felt unable to leave the house because they were worried about negative behaviours towards them.

Many Australians have little knowledge about autism and limited interaction with autistic people. Generally, public attitudes will be shaped by news coverage, online articles and mainstream movies and shows. While media portrayals of autism can positively influence public knowledge, they can also contribute to misunderstanding and increase stigma. It seems the results are mixed.

Studies have found media representations of autism can contribute to stereotypes of what it means to be autistic. For instance, shows such as The Good Doctor and Atypical present autism as a condition of “high functioning, socially deficient, emotionally detached, and heterosexual males from middle-class white families”.

As an autistic person, one of the most disturbing things for me is how marginalised our voices are in conversations about autism. You will most often find non-autistic people behind autism-related research, books, movies and TV programs. Most autistic characters are also played by non-autistic actors.

A review of autism-related news published in Australian print media from 2016 to 2018 found only 16 of 1,351 stories included firsthand perspectives from autistic people.

My own research into depictions of autism in print news published between 1996 and 2005 found narratives of autistic people as dangerous and uncontrollable, or unloved and poorly treated.

When autism met TikTok

TikTok has given many autistic people a much-needed platform to speak about autism in creative ways. Some users such as Paige Layle and Nicole Parish have more than 2 million followers. The opportunity to dispel myths and share the diversity of autistic experiences has not been squandered.

Some of the positives for autistic users include opportunities to:

- connect with others who are similar to us, and feel less isolated and alone

- educate people about some of the lesser known or misunderstood aspects of autism, such as stimming (self-stimulatory behaviour including repetitive or unusual body movement or noises)

- share our passions and interests with others (#SpecialInterest) and

- raise awareness of the prevalence of and different presentation of autism in females (#AutisticGirl).

However, as with all forms of social media, we should exercise caution before labelling TikTok as the solution to autism exclusion.

The other side of it

The most obvious risk is cyberbullying. Many of us will remember the disturbing fad of “faking autism” videos on TikTok. Examples of this included non-autistic people stimming to music (pretending to be autistic), to make people laugh, or because they thought it made them seem cute or quirky.

Turning the autistic experience into a “meme” downplays both our challenges and our strengths. It’s hard to describe just how hurtful it is to see your identity used as a joke to entertain others.

Related to this is the posting of videos of autistic people by others without their consent. Whether this is playground bullies tormenting an autistic person, strangers in a shopping centre filming a “naughty kid”, or a parent having a bad day with their autistic child – these videos can be used, reused and misused by others.

Moderation by TikTik is an additional concern. In 2019, Netzpolitik.org reported TikTok had policies for moderators to suppress certain content by users they thought were “susceptible to harassment or cyberbullying based on their physical or mental condition”.

This included users with “facial disfigurement”, “autism” and “Down syndrome”. A TikTok spokesperson said this was a “blunt and temporary policy” made “in response to an increase in bullying on the app”.

Is the best solution to bullying to silence the voices of potential victims, rather than the bullies?

Algorithmic influence

TikTok’s algorithm is highly curated to individual users. The app decides what videos to show a user based on: their previous interactions including which videos they watch, like and favourite; video information (such as captions and hashtags); and their device and account settings.

This means users will likely see their own perspectives and beliefs reflected back to them. Autistic people may begin to believe this is the only reality that exists, leading to the creation of a “false reality”.

On TikTok, autistic people see an idyllic world where everyone understands and embraces autism. We forget that outside our “echo chamber” there is a world of people living in their own echo chambers.

If we want to see genuine improvement, we have to make autism acceptance and inclusion a priority across public life. We could start by including more autistic voices in TV shows, movies, books and news, as well as more representation in leadership teams and among policy makers.

Sandra Jones, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Research Impact, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

0 comments:

Post a Comment