The Australian government is launching an offensive against cybercriminals, following a data breach that has exposed millions of people’s personal information.

On November 12, Minister for Cyber Security Clare O'Neil announced a taskforce to “hack the hackers” behind the recent Medibank data breach.

The taskforce will be a first-of-its-kind permanent, joint collaboration between Australian Federal Police and the Australian Signals Directorate. Its 100 or so operatives will use the same cyber weapons and tactics as cybercriminals use, to hunt them down and eliminate them as a threat.

Details on how the taskforce will operate remain murky, partly because it needs to keep this information away from criminals. But the fact remains that taking an offensive stance, while it could deter further attacks, could also put a big red cross on Australia’s back.

Australia punches back

It was only in 2016 that the Australian government first publicly acknowledged it has offensive cyber capabilities housed in the Australian Signals Directorate – and that these are used against offshore cybercriminals. The admission came from then prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, following attacks on the Bureau of Meteorology and Department of Parliamentary Services.

Australia has used cyber offensive strategies a number of times in the past. This has included operations against ISIS and, more recently, efforts to disable scammers’ infrastructure and access to stolen data at the start of the pandemic. Details of intelligence operations are generally kept under wraps, especially where the Australian Signals Directorate is involved.

How might the taskforce operate?

Minister O'Neil has said the new taskforce will:

scour the world, hunt down the criminal syndicates and gangs who are targeting Australia in cyber attacks and disrupt their efforts.

As to whether it could launch a counterattack on the Medibank hackers, the resources are there, but working out the kinks will be crucial. Australia’s intelligence agencies have more resources than the average organised cyber gang, not to mention connections to other advanced intelligence agencies around the world.

However, one key issue with holding cybercriminals to account is attribution. A legitimate counterattack requires identifying the source of an attack beyond reasonable doubt. The Medibank data leak has been attributed to criminals based in Russia – most likely from, or at least associated with, the REvil cyber gang.

This assumption is based on similarities between existing REvil sites on the dark web and the extortion site hosting the stolen Medibank data, as well as other similarities between the Medibank attack and REvil’s previous attacks.

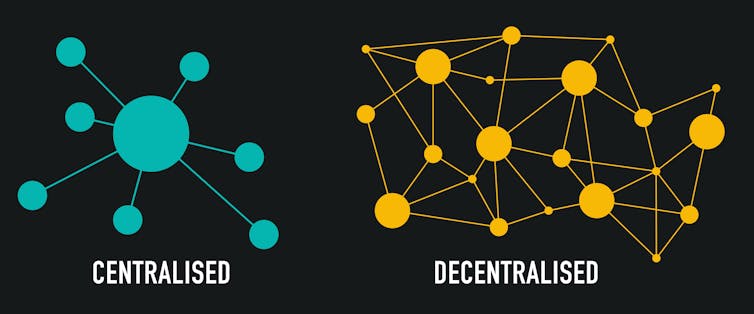

That said, hackers can hide their identity by routing through (often unaware) third parties. So even if this attack is attributable to REvil, or its close associates, the attackers could easily deny involvement if taken to court.

The group could say its systems were used as unwitting hosts by another external perpetrator. Plausible deniability can almost always be maintained in such cases. Russia (and China) have had a track record of denying involvement in cyber espionage.

As such, it’s very difficult to prosecute cybercriminals – especially in cases where these criminals may be backed (officially or unofficially) by their government. And if perpetrators can’t be put behind bars, they can simply lie low for a while before popping up somewhere else in cyberspace.

Beyond the Medibank hackers, the taskforce will also target other potential threats to Australia. In the case of inaccurate attribution in any of these operations, we might see tit-for-tat escalation. In a worst-case scenario, attacks based on incorrect attribution could start a cyberwar with another country.

Defence before offence

By actively seeking and trying to neutralise offshore gangs, Australia will put a target on its back. Russian-linked criminal gangs and others might be encouraged to retaliate and target our sectors, including critical infrastructure.

Boosting Australia’s cyber defences should be the top priority – arguably more so than retaliating. Especially since, even if the taskforce successfully mounts a counterattack on the Medibank hackers, it’s unlikely to recover any data stolen (since criminals make copies of stolen data).

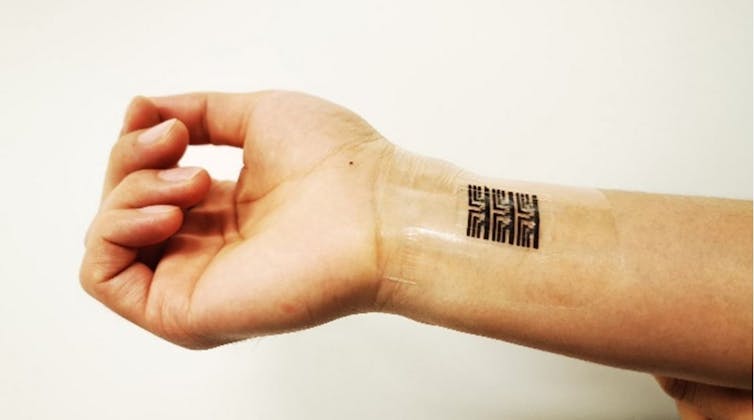

Going after cybercriminals addresses the symptoms of the problem, not the root: the fact that our systems were vulnerable enough to be hacked in the first place. The Medibank breach, and the major Optus breach preceding it, have both demonstrated that even businesses with seemingly strong cybersecurity protocols are vulnerable to attacks.

The best option from a rational and technical standpoint is to prevent, as much as possible, data being stolen in the first place. It might not be as flashy a solution, but it’s the best one in the longer term.![]()

Mamoun Alazab, Associate Professor, College of Engineering, IT and Environment, Charles Darwin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Twitter itself produces a lot of data that’s available nowhere else.

Twitter itself produces a lot of data that’s available nowhere else.