Investing in customisable, open-source software solutions allows nonprofits to grow their programmes faster and at lower costs.

The proverb ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ rings true for India’s social sector now more than ever before. Unable to support their communities in person during the COVID-19 pandemic, nonprofits found new creative solutions to deliver programmes and connect with the people they serve. Almost overnight, digital technologies such as Zoom and WhatsApp became a mainstay of how the social sector works.

WhatsApp, in particular, was used by several nonprofits to send out relevant information and resources, collect feedback, and have conversations free of charge. The shift to WhatsApp was a relatively easy one since India has nearly 400 million active monthly users—the highest in the world. And so organisations didn’t have to spend time convincing people to adopt a new app. They were able to easily leverage WhatsApp to move ahead with their work, whether it was enabling digital learning or providing access to healthcare services.

However, despite the convenience of WhatsApp, it can prove cumbersome after a certain point. Let’s take the example of The Apprentice Project, a nonprofit running education programmes for schoolchildren. When the pandemic hit and schools shut, they could no longer deliver lesson plans within the classroom and had to completely overhaul how they ran their programme. After trying out multiple platforms such as Google Classroom and Edmodo with limited success, they finally turned to WhatsApp. They found that WhatsApp helped them reach a larger number of students across multiple geographies. Students were also more likely to respond as it was a system with which they were already somewhat familiar. However, they hit a few roadblocks fairly quickly: there is an upper limit on the maximum number of contacts in a group; only the person with the phone number can manage the account, and it doesn’t allow the organisation to collect structured data. For organisations like The Apprentice Project, which have hundreds of students within their network, manually managing WhatsApp groups proved to be neither scalable nor cost-effective or sustainable.

Nonprofits use Glific for different needs—from providing information to building long-term engagement with communities and creating behaviour change.

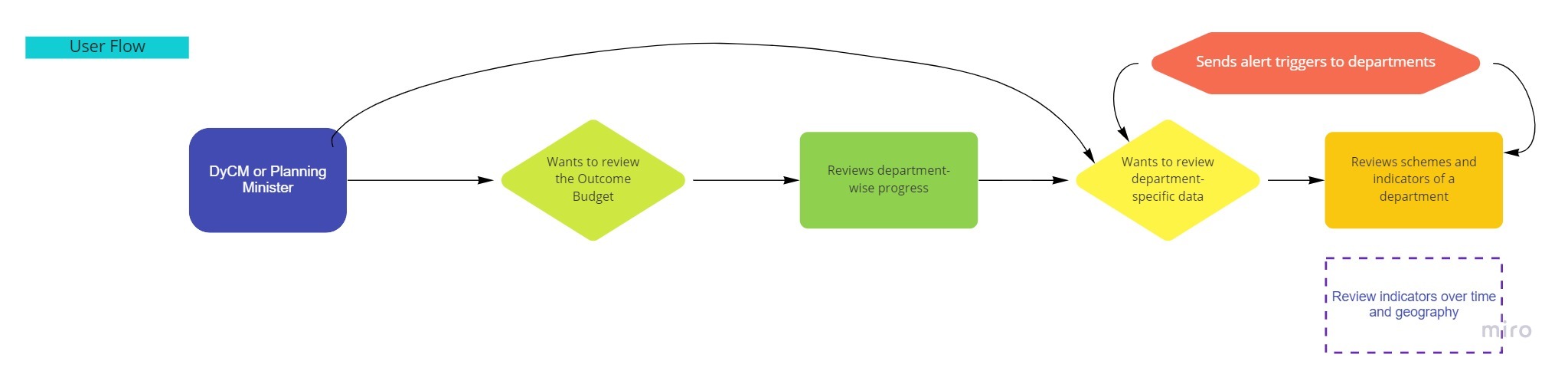

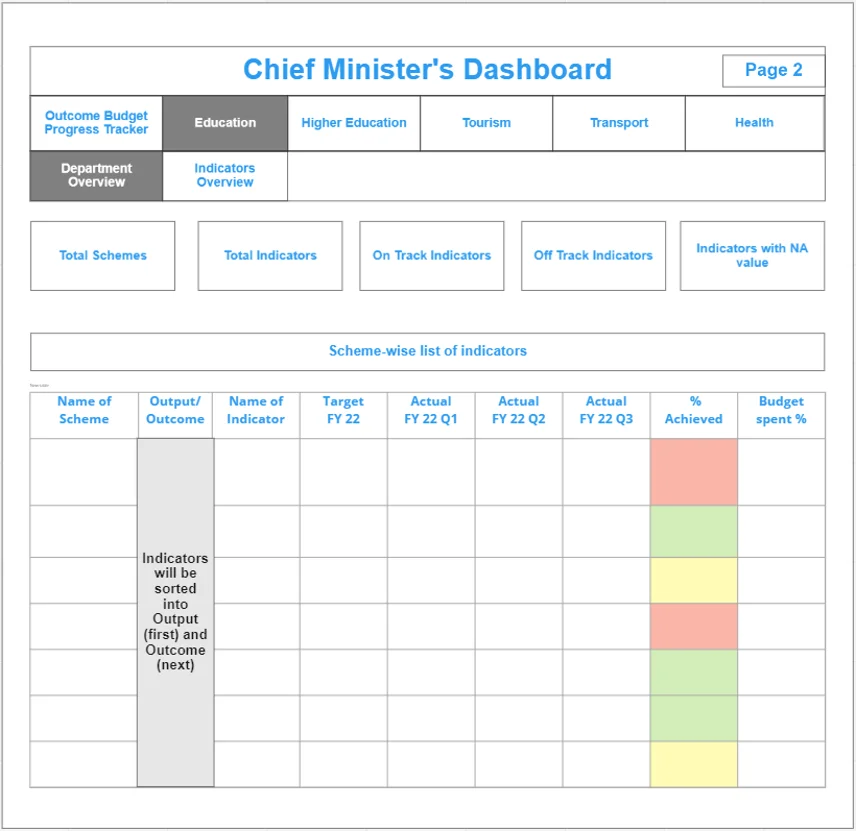

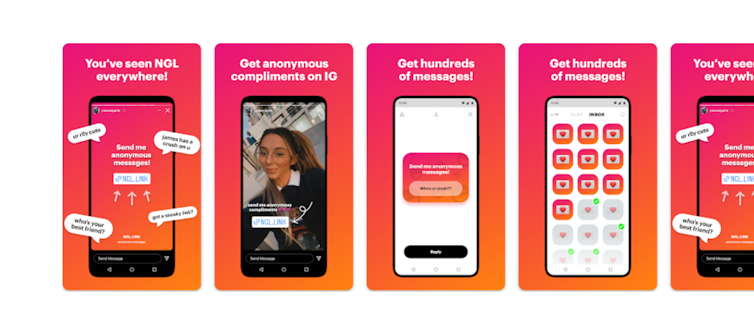

Recognising these communication challenges that nonprofits faced, Project Tech4Dev designed Glific, an open-source, WhatsApp-based communication platform that organisations can use for two-way communication with their communities. By automating large parts of the conversation, it allows nonprofits to communicate with thousands of people, while also reducing the burn on their resources. Additionally, Glific supports multiple Indian languages and can be integrated with other apps such as Google Sheets for data monitoring and analysis.

Today 32 nonprofits use Glific for different needs—from providing information to building long-term engagement with communities and creating behaviour change. For instance, MukkaMaar has been using it to train young girls about the physical and non-physical aspects of self-defence and development. Reap Benefit, on the other hand, has been using Glific to engage with citizens to solve societal problems. Another organisation, Slam Out Loud, sends art-based activities to children that they can complete at any time of the day, whenever they have digital access.

Custom versus customised

When organisations do decide to invest resources into technology, they often look at building custom solutions from scratch, such as apps, websites, and platforms, in response to a very specific problem. For instance, an education organisation that trains teachers doesn’t need to build a custom tech solution to communicate with them and share resources and materials, especially when there are many other organisations that might employ a tech solution for the same use case. Moreover, a custom solution might work at a certain scale, but may not be sufficient at a much larger scale, or in a different context.

Given this, investing in highly specific tech solutions to problems faced by many is a strategy with many limitations. A more effective use of time and resources would be to build an open-source solution that solves a problem for many and can then be customised to the unique needs of each nonprofit or sector. Such solutions work out better in the long run for the organisation implementing them as well as for other nonprofits who might face similar problems.

A case for open-source technology

To build a more collaborative and impactful social sector, we need to build an ecosystem of open-source technology creators and users. When a software is open-source, it is publicly available and can be modified based on one’s needs, often for free or at a nominal cost. Using existing open-source software can allow nonprofits to grow their programmes faster, and at lower costs.

Different nonprofits will use technology in different ways. Some might use it to send out information, others might want it to track progress and gather feedback, and so on. While all of these features might not be available in the basic version of a software, the advantage of open-source technology is that users can customise it to their requirements.

This is what happened in the case of Digital Green, a nonprofit working to empower smallholder farmers through technology. As part of their work with chilli farmers in Andhra Pradesh, they used a text-based chatbot on WhatsApp to send information about crop protection to farmers and answer any questions they might have. Soon they realised that typing responses was a barrier for many farmers. And so Glific worked with them to create a voice-based chatbot, which allowed farmers to record and send voice notes in their local language.

The reason we were able to quickly integrate a voice feature into the existing platform was that all the other necessary features were already present, making the process faster and less resource intensive. Not only did this feature benefit Digital Green, but it is also now available to any other nonprofit in the ecosystem that is looking for something similar. As the ecosystem develops and more nonprofits articulate their needs, additional features will continue to get added. Over time, as new customisations are added to the basic tool, the product evolves to encompass a range of features that can be used across organisations working on different issues. With each round of customisation, the cost and time taken to develop the product also keeps reducing, making the whole process self-propagating, scalable, and sustainable.

Had an organisation such as Digital Green decided to go to the market and build a custom software unique to their needs, it would have taken a lot more time and resources. Additionally, when thinking about customising open-source software versus building custom solutions, it is helpful to remember that building a new software from scratch requires creating a whole ecosystem of regular maintenance, updates, and management.

For nonprofits, it is no longer a question of online versus offline.

Using software as a service (SaaS) solutions such as Glific—where the nonprofit simply pays for the service and all the product design and maintenance is taken care of by the software organisation—usually comes with pre-built systems, which are much faster to deploy, both within the organisation and in programme implementation. For example, if a nonprofit decides to use WhatsApp, they can begin implementing their communication strategy within a few days, as opposed to if they had to learn about and get their communities to use an entirely new software tool.

For nonprofits, it is no longer a question of online versus offline. The pandemic has pushed them to think about integrating digital solutions into their operations. Harnessing technology allows organisations to reinforce their in-person communication at multiple points, using multiple channels. Programme delivery and engagement will be more effective and powerful by sending a WhatsApp message to follow up after a door-to-door visit.

Using open-source technology to scale communications can be transformative for both large and small nonprofits, allowing them to work more efficiently and effectively. For organisations that might be wary, intimidated by, or sceptical of technology, starting small is the way to go. It’s also not necessary to have a team of tech experts, especially if the nonprofit does not have the resources to invest in one. However, what is important is that nonprofits should be able to articulate their key issues, problems, needs, and goals clearly so that they can work with software vendors and developers to come up with solutions or customise existing tools that work for them. This will strengthen not only their work, but also the sector as a whole.

This is the fifth article in an 8-part series which seeks to build a knowledge base on using technology for social good.